Common Python Data Structures (Guide) – Real Python

Dictionaries, Maps, and Hash Tables

In Python, dictionaries(or dicts for short) are a central data structure. Dicts store an arbitrary number of objects, each identified by a unique dictionary key.

Dictionaries are also often called maps, hashmaps, lookup tables, or associative arrays. They allow for the efficient lookup, insertion, and deletion of any object associated with a given key.

Phone books make a decent real-world analog for dictionary objects. They allow you to quickly retrieve the information (phone number) associated with a given key (a person’s name). Instead of having to read a phone book front to back to find someone’s number, you can jump more or less directly to a name and look up the associated information.

This analogy breaks down somewhat when it comes to how the information is organized to allow for fast lookups. But the fundamental performance characteristics hold. Dictionaries allow you to quickly find the information associated with a given key.

Dictionaries are one of the most important and frequently used data structures in computer science. So, how does Python handle dictionaries? Let’s take a tour of the dictionary implementations available in core Python and the Python standard library.

dict: Your Go-To Dictionary

Because dictionaries are so important, Python features a robust dictionary implementation that’s built directly into the core language: the dict data type.

Python also provides some useful syntactic sugar for working with dictionaries in your programs. For example, the curly-brace ({ }) dictionary expression syntax and dictionary comprehensions allow you to conveniently define new dictionary objects:

phonebook = {... "bob": 7387,... "alice": 3719,... "jack": 7052,... }

squares = {x: x * x for x in range(6)}

phonebook["alice"]3719

squares

{0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25}There are some restrictions on which objects can be used as valid keys.

Python’s dictionaries are indexed by keys that can be of any hashable type. A hashable object has a hash value that never changes during its lifetime (see __hash__), and it can be compared to other objects (see __eq__). Hashable objects that compare as equal must have the same hash value.

Immutable types like strings and numbers are hashable and work well as dictionary keys. You can also use tuple objects as dictionary keys as long as they contain only hashable types themselves.

For most use cases, Python’s built-in dictionary implementation will do everything you need. Dictionaries are highly optimized and underlie many parts of the language. For example, class attributes and variables in a stack frame are both stored internally in dictionaries.

Python dictionaries are based on a well-tested and finely tuned hash table implementation that provides the performance characteristics you’d expect: O(1) time complexity for lookup, insert, update, and delete operations in the average case.

There’s little reason not to use the standard dict implementation included with Python. However, specialized third-party dictionary implementations exist, such as skip lists or B-tree–based dictionaries.

Besides plain dict objects, Python’s standard library also includes a number of specialized dictionary implementations. These specialized dictionaries are all based on the built-in dictionary class (and share its performance characteristics) but also include some additional convenience features.

Let’s take a look at them.

collections.OrderedDict: Remember the Insertion Order of Keys

Python includes a specialized dict subclass that remembers the insertion order of keys added to it: collections.OrderedDict.

Note: OrderedDict is not a built-in part of the core language and must be imported from the collections module in the standard library.

While standard dict instances preserve the insertion order of keys in CPython 3.6 and above, this was simply a side effect of the CPython implementation and was not defined in the language spec until Python 3.7. So, if key order is important for your algorithm to work, then it’s best to communicate this clearly by explicitly using the OrderedDict class:

import collections

d = collections.OrderedDict(one=1, two=2, three=3)

d

OrderedDict([('one', 1), ('two', 2), ('three', 3)])

d["four"] = 4

d

OrderedDict([('one', 1), ('two', 2),('three', 3), ('four', 4)])

d.keys()

odict_keys(['one', 'two', 'three', 'four'])Until Python 3.8, you couldn’t iterate over dictionary items in reverse order using reversed(). Only OrderedDict instances offered that functionality. Even in Python 3.8, dict and OrderedDict objects aren’t exactly the same. OrderedDict instances have a .move_to_end() method that is unavailable on plain dict instance, as well as a more customizable .popitem() method than the one plain dict instances.

collections.defaultdict: Return Default Values for Missing Keys

The defaultdict class is another dictionary subclass that accepts a callable in its constructor whose return value will be used if a requested key cannot be found.

This can save you some typing and make your intentions clearer as compared to using get() or catching a KeyError exception in regular dictionaries:

from collections import defaultdict

dd = defaultdict(list)# Accessing a missing key creates it and# initializes it using the default factory,# i.e. list() in this example:

dd["dogs"].append("Rufus")

dd["dogs"].append("Kathrin")

dd["dogs"].append("Mr Sniffles")

dd["dogs"]['Rufus', 'Kathrin', 'Mr Sniffles']collections.ChainMap: Search Multiple Dictionaries as a Single Mapping

The collections.ChainMap data structure groups multiple dictionaries into a single mapping. Lookups search the underlying mappings one by one until a key is found. Insertions, updates, and deletions only affect the first mapping added to the chain:

from collections import ChainMap

dict1 = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

dict2 = {"three": 3, "four": 4}

chain = ChainMap(dict1, dict2)

chain

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2}, {'three': 3, 'four': 4})# ChainMap searches each collection in the chain# from left to right until it finds the key (or fails):

chain["three"]3

chain["one"]1

chain["missing"]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 'missing'types.MappingProxyType: A Wrapper for Making Read-Only Dictionaries

MappingProxyType is a wrapper around a standard dictionary that provides a read-only view into the wrapped dictionary’s data. This class was added in Python 3.3 and can be used to create immutable proxy versions of dictionaries.

MappingProxyType can be helpful if, for example, you’d like to return a dictionary carrying internal state from a class or module while discouraging write access to this object. Using MappingProxyType allows you to put these restrictions in place without first having to create a full copy of the dictionary:

from types import MappingProxyType

writable = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

read_only = MappingProxyType(writable)# The proxy is read-only:

read_only["one"]1

read_only["one"] = 23

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'mappingproxy' object does not support item assignment

# Updates to the original are reflected in the proxy:

writable["one"] = 42

read_only

mappingproxy({'one': 42, 'two': 2})Dictionaries in Python: Summary

All the Python dictionary implementations listed in this tutorial are valid implementations that are built into the Python standard library.

If you’re looking for a general recommendation on which mapping type to use in your programs, I’d point you to the built-in dict data type. It’s a versatile and optimized hash table implementation that’s built directly into the core language.

I would recommend that you use one of the other data types listed here only if you have special requirements that go beyond what’s provided by dict.

All the implementations are valid options, but your code will be clearer and easier to maintain if it relies on standard Python dictionaries most of the time.

Array Data Structures

An array is a fundamental data structure available in most programming languages, and it has a wide range of uses across different algorithms.

In this section, you’ll take a look at array implementations in Python that use only core language features or functionality that’s included in the Python standard library. You’ll see the strengths and weaknesses of each approach so you can decide which implementation is right for your use case.

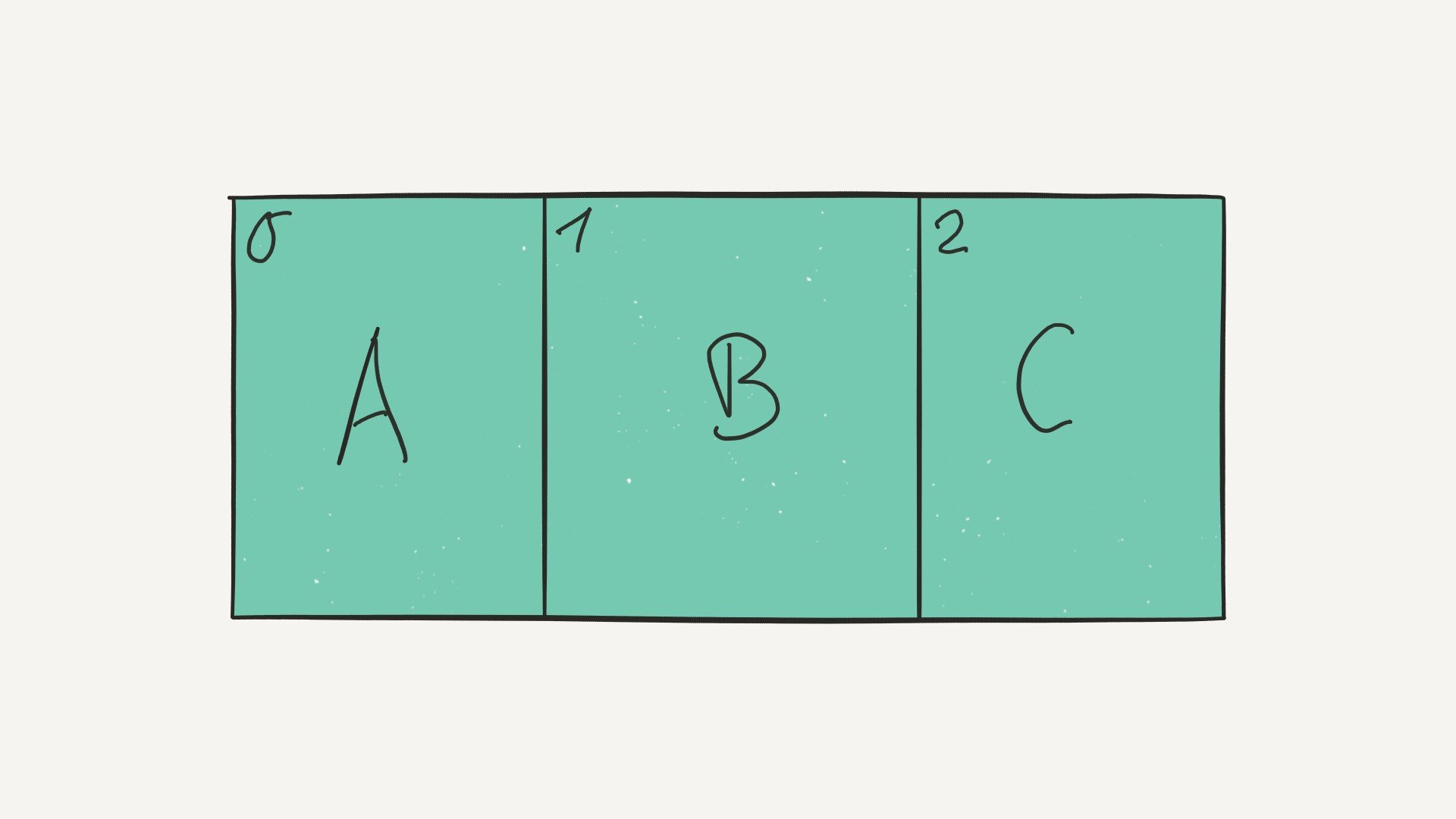

But before we jump in, let’s cover some of the basics first. How do arrays work, and what are they used for? Arrays consist of fixed-size data records that allow each element to be efficiently located based on its index:

Because arrays store information in adjoining blocks of memory, they’re considered contiguous data structures (as opposed to linked data structures like linked lists, for example).

A real-world analogy for an array data structure is a parking lot. You can look at the parking lot as a whole and treat it as a single object, but inside the lot there are parking spots indexed by a unique number. Parking spots are containers for vehicles—each parking spot can either be empty or have a car, a motorbike, or some other vehicle parked on it.

But not all parking lots are the same. Some parking lots may be restricted to only one type of vehicle. For example, a motor home parking lot wouldn’t allow bikes to be parked on it. A restricted parking lot corresponds to a typed array data structure that allows only elements that have the same data type stored in them.

Performance-wise, it’s very fast to look up an element contained in an array given the element’s index. A proper array implementation guarantees a constant O(1) access time for this case.

Python includes several array-like data structures in its standard library that each have slightly different characteristics. Let’s take a look.

list: Mutable Dynamic Arrays

Lists are a part of the core Python language. Despite their name, Python’s lists are implemented as dynamic arrays behind the scenes.

This means a list allows elements to be added or removed, and the list will automatically adjust the backing store that holds these elements by allocating or releasing memory.

Python lists can hold arbitrary elements—everything is an object in Python, including functions. Therefore, you can mix and match different kinds of data types and store them all in a single list.

This can be a powerful feature, but the downside is that supporting multiple data types at the same time means that data is generally less tightly packed. As a result, the whole structure takes up more space:

arr = ["one", "two", "three"]

arr[0]'one'# Lists have a nice repr:

arr

['one', 'two', 'three']# Lists are mutable:

arr[1] = "hello"

arr

['one', 'hello', 'three']del arr[1]

arr

['one', 'three']# Lists can hold arbitrary data types:

arr.append(23)

arr

['one', 'three', 23]tuple: Immutable Containers

Just like lists, tuples are part of the Python core language. Unlike lists, however, Python’s tuple objects are immutable. This means elements can’t be added or removed dynamically—all elements in a tuple must be defined at creation time.

Tuples are another data structure that can hold elements of arbitrary data types. Having this flexibility is powerful, but again, it also means that data is less tightly packed than it would be in a typed array:

arr = ("one", "two", "three")

arr[0]'one'# Tuples have a nice repr:

arr

('one', 'two', 'three')# Tuples are immutable:

arr[1] = "hello"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

del arr[1]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object doesn't support item deletion

# Tuples can hold arbitrary data types:# (Adding elements creates a copy of the tuple)

arr + (23,)('one', 'two', 'three', 23)array.array: Basic Typed Arrays

Python’s array module provides space-efficient storage of basic C-style data types like bytes, 32-bit integers, floating-point numbers, and so on.

Arrays created with the array.array class are mutable and behave similarly to lists except for one important difference: they’re typed arrays constrained to a single data type.

Because of this constraint, array.array objects with many elements are more space efficient than lists and tuples. The elements stored in them are tightly packed, and this can be useful if you need to store many elements of the same type.

Also, arrays support many of the same methods as regular lists, and you might be able to use them as a drop-in replacement without requiring other changes to your application code.

import array

arr = array.array("f", (1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5))

arr[1]1.5# Arrays have a nice repr:

arr

array('f', [1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5])# Arrays are mutable:

arr[1] = 23.0

arr

array('f', [1.0, 23.0, 2.0, 2.5])del arr[1]

arr

array('f', [1.0, 2.0, 2.5])

arr.append(42.0)

arr

array('f', [1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 42.0])# Arrays are "typed":

arr[1] = "hello"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: must be real number, not strstr: Immutable Arrays of Unicode Characters

Python 3.x uses str objects to store textual data as immutable sequences of Unicode characters. Practically speaking, that means a str is an immutable array of characters. Oddly enough, it’s also a recursive data structure—each character in a string is itself a str object of length 1.

String objects are space efficient because they’re tightly packed and they specialize in a single data type. If you’re storing Unicode text, then you should use a string.

Because strings are immutable in Python, modifying a string requires creating a modified copy. The closest equivalent to a mutable string is storing individual characters inside a list:

arr = "abcd"

arr[1]'b'

arr

'abcd'# Strings are immutable:

arr[1] = "e"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

del arr[1]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object doesn't support item deletion

# Strings can be unpacked into a list to# get a mutable representation:list("abcd")['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']"".join(list("abcd"))'abcd'# Strings are recursive data structures:type("abc")"<class 'str'>"type("abc"[0])"<class 'str'>"bytes: Immutable Arrays of Single Bytes

bytes objects are immutable sequences of single bytes, or integers in the range 0 ≤ x ≤ 255. Conceptually, bytes objects are similar to str objects, and you can also think of them as immutable arrays of bytes.

Like strings, bytes have their own literal syntax for creating objects and are space efficient. bytes objects are immutable, but unlike strings, there’s a dedicated mutable byte array data type called bytearray that they can be unpacked into:

arr = bytes((0, 1, 2, 3))

arr[1]1# Bytes literals have their own syntax:

arr

b'\x00\x01\x02\x03'

arr = b"\x00\x01\x02\x03"# Only valid `bytes` are allowed:bytes((0, 300))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: bytes must be in range(0, 256)# Bytes are immutable:

arr[1] = 23

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'bytes' object does not support item assignment

del arr[1]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'bytes' object doesn't support item deletionbytearray: Mutable Arrays of Single Bytes

The bytearray type is a mutable sequence of integers in the range 0 ≤ x ≤ 255. The bytearray object is closely related to the bytes object, with the main difference being that a bytearray can be modified freely—you can overwrite elements, remove existing elements, or add new ones. The bytearray object will grow and shrink accordingly.

A bytearray can be converted back into immutable bytes objects, but this involves copying the stored data in full—a slow operation taking O(n) time:

arr = bytearray((0, 1, 2, 3))

arr[1]1# The bytearray repr:

arr

bytearray(b'\x00\x01\x02\x03')# Bytearrays are mutable:

arr[1] = 23

arr

bytearray(b'\x00\x17\x02\x03')

arr[1]23# Bytearrays can grow and shrink in size:del arr[1]

arr

bytearray(b'\x00\x02\x03')

arr.append(42)

arr

bytearray(b'\x00\x02\x03*')# Bytearrays can only hold `bytes`# (integers in the range 0 <= x <= 255)

arr[1] = "hello"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'str' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

arr[1] = 300

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: byte must be in range(0, 256)# Bytearrays can be converted back into bytes objects:# (This will copy the data)bytes(arr)b'\x00\x02\x03*'Arrays in Python: Summary

There are a number of built-in data structures you can choose from when it comes to implementing arrays in Python. In this section, you’ve focused on core language features and data structures included in the standard library.

If you’re willing to go beyond the Python standard library, then third-party packages like NumPy and pandas offer a wide range of fast array implementations for scientific computing and data science.

If you want to restrict yourself to the array data structures included with Python, then here are a few guidelines:

- If you need to store arbitrary objects, potentially with mixed data types, then use a

listor atuple, depending on whether or not you want an immutable data structure. - If you have numeric (integer or floating-point) data and tight packing and performance is important, then try out

array.array. - If you have textual data represented as Unicode characters, then use Python’s built-in

str. If you need a mutable string-like data structure, then use alistof characters. - If you want to store a contiguous block of bytes, then use the immutable

bytestype or abytearrayif you need a mutable data structure.

In most cases, I like to start out with a simple list. I’ll only specialize later on if performance or storage space becomes an issue. Most of the time, using a general-purpose array data structure like list gives you the fastest development speed and the most programming convenience.

I’ve found that this is usually much more important in the beginning than trying to squeeze out every last drop of performance right from the start.

Records, Structs, and Data Transfer Objects

Compared to arrays, record data structures provide a fixed number of fields. Each field can have a name and may also have a different type.

In this section, you’ll see how to implement records, structs, and plain old data objects in Python using only built-in data types and classes from the standard library.

Note: I’m using the definition of a record loosely here. For example, I’m also going to discuss types like Python’s built-in tuple that may or may not be considered records in a strict sense because they don’t provide named fields.

Python offers several data types that you can use to implement records, structs, and data transfer objects. In this section, you’ll get a quick look at each implementation and its unique characteristics. At the end, you’ll find a summary and a decision-making guide that will help you make your own picks.

Note: This tutorial is adapted from the chapter “Common Data Structures in Python” in Python Tricks: The Book. If you enjoy what you’re reading, then be sure to check out the rest of the book.

Alright, let’s get started!

dict: Simple Data Objects

As mentioned previously, Python dictionaries store an arbitrary number of objects, each identified by a unique key. Dictionaries are also often called maps or associative arrays and allow for efficient lookup, insertion, and deletion of any object associated with a given key.

Using dictionaries as a record data type or data object in Python is possible. Dictionaries are easy to create in Python as they have their own syntactic sugar built into the language in the form of dictionary literals. The dictionary syntax is concise and quite convenient to type.

Data objects created using dictionaries are mutable, and there’s little protection against misspelled field names as fields can be added and removed freely at any time. Both of these properties can introduce surprising bugs, and there’s always a trade-off to be made between convenience and error resilience:

car1 = {... "color": "red",... "mileage": 3812.4,... "automatic": True,... }

car2 = {... "color": "blue",... "mileage": 40231,... "automatic": False,... }# Dicts have a nice repr:

car2